Zardoz, The Wicker Man and Jorge Luis Borges - on knowledge, alienation and messianic violence

"Knowledge is not enough."

"Here, man and the sum of his knowledge will never die, but go forward to perfection."

As a lover of cult 70s films (you can mainly thank the David Rudkin’s Penda’s Fen and Andrei Tarkovsky’s Mirror for that) it might surprise you to know that it was only in the past couple of weeks I watched two classics of the genre, The Wicker Man (1973) and Zardoz (1974).

Both live up to their cult classic reputations in their own right, but I was struck by how they are both about outsiders entering an enclosed society that is totally alien to them, only to find out their arrival has been planned all along, becoming messianic figures who are used as a catalyst for the transformation of each society from stagnation and ruin to a new epoch. I didn’t set out to do some comparative literary analysis, but I found a thread I wanted to pull at, particularly how systems surrounding the production, preservation and reproduction of knowledge and belief play a key role in differentiating social groups and reinforcing the hierarchies within and between them.

I've been reading Jorge Louis Borges' collection of short stories, Fictions, is filled with the manifold implications and anxieties around the preservation and production of knowledge in an age where the amount of knowledge accumulated nears infinity. This manifests in literary labyrinths and paper trails through which the protagonists feel the obsessive pull towards a sublime that can never be found but only tantalisingly glimpsed, a piece of knowledge through which all knowledge could be comprehended and catalogued. In The Library of Babel, a library filled with books that contain every possible combination of letters creates generations of people into a religious fervour to find meaning out of the chaos. In Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius, the author pulls at a small thread that unravels an encyclopaedia of a fictional world with its own strange philosophies, which begin to replace our own. In Funes, His Memory, a child gains the ability of perfect memory and pictorial recollection but without the capacity to think about anything in abstract terms, leaving him restless and incompatible with the world around him.

Anxieties around the pursuit of meaning within oceans of knowledge and the capacity to preserve it are essential to the story of Zardoz, to the extent that it could plausibly be a Borges story if he had gone out of his way to emulate HG Wells’ The Time Machine or even Conan the Barbarian.

Set in the far future of 2293, 'Brutes' live in an apocalyptic wasteland, their populations managed by Exterminators, who offer tribute to a mysterious god known as Zardoz. An Exterminator named Zed (Sean Connery) sneaks his way into an enclave, Vortex 4, that is a paradise where live the Eternals (an assortment of all the smokeshow 70s models), the next stage of humanity’s evolution with psychic powers and the ‘gift’ of immortality. Sustaining themselves with the tributes made by the Brutes, they act as the keepers of a repository of knowledge of all human history.

"We few... the rich, the powerful, the clever...cut ourselves off to guard the knowledge and treasures of civilisation, as the world plunged into a dark age. To do this, we had to harden our hearts against the suffering outside. We are custodians of the past for an unknown future."

What this film made me think about was how the acts of preservation and archival of knowledge create their own systems of social relations according to who has access to it (Eternals vs Brutes), and ultimately will generate new methodologies of understanding and interpreting such knowledge. Knowledge, much like radical belief, alienates one social group from the other, reifying an already-existing hierarchy of exploitation and stratification. And yet, knowledge itself is *not enough* to preserve the beautiful and immortal bourgeoise class of this society from stagnation, mutual distrust and complete disassociation from the world around you - there is a stable full of zombie-like 'Apathetics'.

Social reproduction has been differed entirely to an artificial intelligence, the Tabernacle, that births them each anew if they happen to die, disposing of the need for sex and an emotional capacity to deal with such feelings. In the small paradise they occupy there is no meaningful future to live for, discontent is severely punished, and nobody feels the urge to create art or anything new at all. The depths of space has been explored, but there’s nothing worthwhile to find. The only desire that remains is the desire for death, which they welcome gladly. In one scene, a cynical Eternal named Friend shows Zed around a room full of statues, part of their repository of knowledge, the “gods, goddesses, kings and queens” who all “died of boredom”. This brought to mind how anticolonial theorist and psychiatrist Franz Fanon in his book The Wretched of the Earth characterised the world of the white coloniser as one that is stuck in its glorification of a dead past:

“The settler makes history and is conscious of making it. And because he constantly refers to the history of his mother country, he clearly indicates that he himself is the extension of that mother country… A world divided into compartments, a motionless, Manicheistic world, a world of statues: the statue of the general who carried out the conquest, the statue of the engineer who built the bridge; a world which is sure of itself, which crushes with its stones the backs flayed by whips: this is the colonial world.”

This is why the oppressed native must learn to realise their dream of action and aggression, of ‘muscular prowess’, to break free of this rigidity. In Zardoz, the white bourgeoisie of the future has achieved full motionlessness, with only their past to admire, and it is up to the gun-toting, chest-bared Zed to bring the Brutes’ deliverance to the Vortex’s entropy. Friend is eventually cast off by the society for his dissent and becomes a Renegade, forced to go undergo forced aging as a punishment, aiding Zed in his quest to bring an end to Vortex 4. As the events that will bring down the enclave are set into motion, Friend admits that

"Knowledge is not enough."

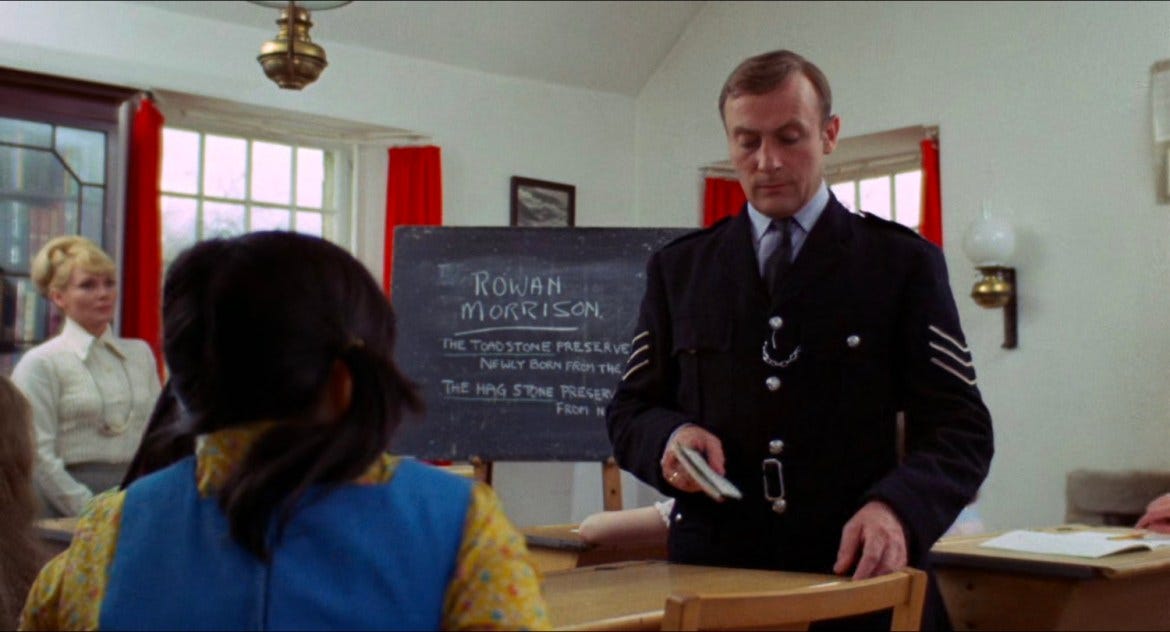

In The Wicker Man, a policeman named Neil Howie arrives on a remote Scottish island in search of a missing girl after being given an anonymous tip-off. A god-fearing Christian, he learns to his dismay that the islanders have taken up paganism, dance around maypoles, have public sex, and engage in all manner of rituals. Howie quickly discovers that something deeply strange is happening, as the islanders lead him up the garden path as to the whereabouts of the missing girl.

It’s frequently describes as a horror film, and so I was surprised to learn how goofy it was - the music of the islanders is inventive and unapologetically joyous, they hold no secrets from each other, and they simply love to dress up and play pranks. This is a society that, unlike Vortex 4, has something to believe in.

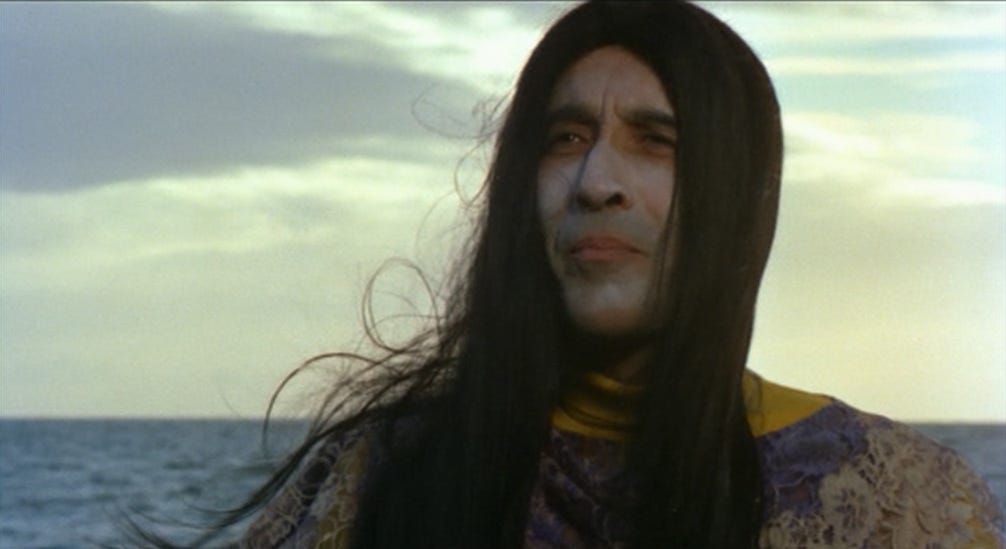

Lord Summerisle (a delightful Christopher Lee) reveals that the island took up paganism after his grandfather bought the island to experiment with fruit growing, taking advantage of the islanders’ labour power and the natural volcanic soil and warm air currents. The Victorian agriculturalist invoked their ancestors’ worship of the old gods and practice of fertility rituals to justify his experiments, and when they prove fruitful, the island begins to reject Christianity en masse and eject their ministers.

“It's most important that each generation born on Summerisle be made aware that here the Gods aren't dead.”

While all the idols of Vortex 4 are long dead, the gods of the sea and the land have a tangible presence for the islanders and enacted through ritual, allowing for communal bonds that are "infinitely more spiritually nourishing than the life-denying, God-terror of the Kirk”, as Lord Summerisle describes. Howie’s sexual anxieties are brought to the fore by the temptations of the pub landlord’s daughter, and he is clearly set on edge by view that the schoolchildren are being taught the wrong kind of knowledge, such as ‘the toadstone preserves the newly born from the weird woman’, and ‘the hag stone preserves people from nightmare.’

What stuck out for me about The Wicker Man was that the straight-laced, audience-surrogate protagonist is as radically religious as the islanders are, just in a very different way. Howie and the islanders as subjects of two completely separate systems of knowledge production are utterly alienated from each other, and it is the imbalance of power that allows the islanders to toy with him. He is just one policeman with no way of getting home, after all. The nature of belief is to make the believer strange and unknowable to other people who do not have the same belief, and the hegemonic cannot abide what is unknown to it for long.

The arrival of Howie turns out to have been orchestrated by Lord Summerisle all along, for he is the sacrificial virgin to be burned in the wicker man and restore the island’s fortunes after a failed harvest the previous year. In parallel with Zardoz, we see how an outsider of a spurned social group is permitted entry back in to initiate a form of system-shock that will either allow for its continued reproduction, or begin a transformation necessary for survival in intolerable conditions.

Given how influential The Wicker Man has been for the concept of ‘folk belief’, it doesn't make any disguises about the fact that what we believe to be ancient and continuous folk practices are just bullshit made up by Victorians. It's all syncretism and anachronisms - the maypole, the green man, the wicker man, sumer is icumin in, Punch (of all things?!) have shit all to do with each other, but that doesn't matter, it's about a narrative that reproduces the social system as a whole. The establishment of the ideological superstructure was a necessary condition for the economic base, and in turn the new economic base allowed for the ideological superstructure to flourish. Knowledge once thought long dead can be preserved in strange ways, and can be resurrected, reconstituted and restructured, with any lacuna filled in with whatever’s to hand, and the world can be made anew.

Knowledge in Zardoz eventually proves to be liberatory. Zed, who has allowed other people to believe that the only things he loves doing are murdering and raping, is allowed to discover a trove of knowledge that shatters the barrier that forms the essential mystification that separates the Brutes and the Eternals, ushering in a transfiguration of the perverted necropolitical order into one that restores life and death as within the bounds of knowledge and understanding, and learns to accommodate for humanity's natural desires.

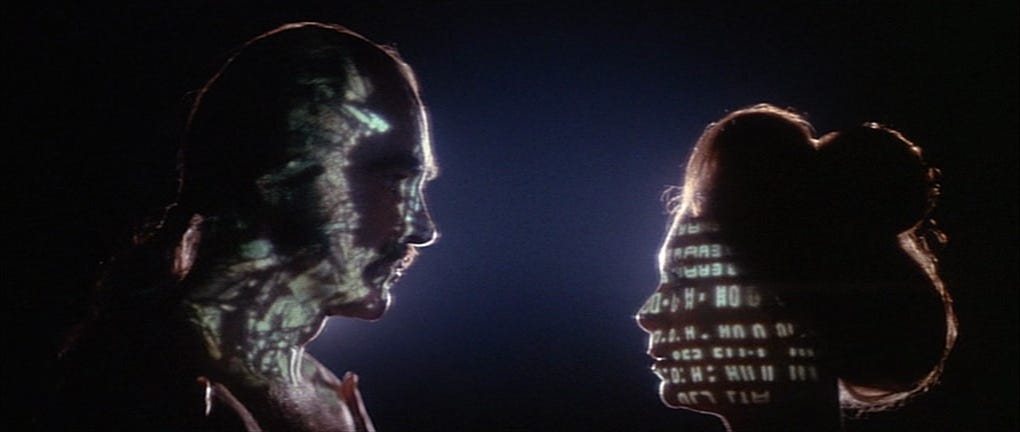

There is a beautifully shot scene where Zed and some Eternals have a weird orgy, and he is given access to their repository of knowledge, which includes not just histories of humanity but its art, which is super imposed on them in a mesmerising montage set to Beethoven’s Seventh that is pure cinema. In this context, the acquisition of knowledge has its vitality and sacredness restored once given the impulse of belief that current organisation of society is not inevitable. The combination of knowledge acquisition and violence in the film’s climax represents what German philosopher Walter Benjamin in On the Concept of History characterises as a moment where the ‘continuum of history’ is utterly shattered. The revolutionary class arrives from outside expected path of history to fulfil its messianic role in disrupting the rigid, homogonous temporality of the bourgeoise, enforced by clocks and calendars, its promise of a slow march towards ‘progress’ a cruel joke. Through their own violence and full realisation of their own past, the oppressed redeem the centuries of domination and violence done unto them.

Not man or men but the struggling, oppressed class itself is the depository of historical knowledge. In Marx it appears as the last enslaved class, as the avenger that completes the task of liberation in the name of generations of the downtrodden.

Like Borges’ librarians who would forever seek out the book that contained the combination of letters that would supply their own personal Vindications, the Eternals find that the deferment of meaning in their existence to the dead, impersonal and external instead seeking fulfilment through social connectivity and interaction, no matter how imperfect and full of friction it may be, is a dead end.

Ultimately, both the preservation and production of knowledge are inseparable from the socio-economic totality in which they occupy, being shaped by and shaping in turn those who preserve and produce knowledge to manage and stabilise existing social relations. But, crucially, there is always the potential for the generative in acquiring knowledge that, if allowed to crystallise, might just change the world.

Closing thoughts

It has been said that there is a certain reactionary element to Zardoz that I can’t disagree with, namely the desire to pull the breaks on social progress and gender liberation lest we become like the strange, sexless and emasculated Eternals, and all it’ll take is a Manly Man™ with a lot of chest hair and a gun to sort it all out. This might be the case, and the final scene emphasises a return to the nuclear family as a representation of normality, but I think it is not a total victory for revanchist hetero-normative patriarchy. Something has changed. a knowledge that the world cannot be returned to as it once was, for there are no distinctions between Brutes or Eternals any more.

The director of The Wicker Man, Robin Hardy, is certainly a small-c conservative, and he has scoffed at the idea that there could be any serious academic or, god forbid, feminist readings of the film. Again, an obvious impulse behind the film to point at could be a desire to reject hippie bullshit, but it’s too well-written of a story to just be that. At the very least, it respects those who want something to believe in, which for this irony-poisoned age is probably just the thing we need.

I hope writing about this small constellation of fiction I've been thinking about recently has made you think, too, and maybe made you want to seek them out if you’ve not watched/read them before. Maybe I'm just trying to assuage my own anxiety about how much there is I want to read and write when there is so little time, and I become paralysed by the sheer amount of obligations and distractions there are in the world. But I think I’m glad that I have many reasons that keep me from chaining myself to my desk and falling into a deep well of my own making.